Wilbur Wright—Why Wilbur Mattered

“It is not necessary to look far into the future; we see enough already to be certain that it will be magnificent.

—Wilbur Wright

|

Two Wrights made the airplane. But they were driven by Wil. Wilbur Wright died before the Engineers Club was conceived. Had he lived it seems certain he would have been not just a founding member but an early and active club president. We include his profile here as a might-have-been member.

The Wright Brothers ~ In Flight includes 1908-1909 flights in the United States, France and Italy – as well as the first motion pictures taken from an airplane. Motion pictures helped convince early skeptics that human flight was real.

© 2009 Martel Art. Video Credits

© 2009 Martel Art. Video Credits

Wilbur Wright--Why Wilbur Mattered

|

Story and art by Mark Martel

Originally published in the Dayton City Paper

At rare intervals a few truly indispensable individuals take us where no one has gone before. A century back in Dayton it was Kettering, Patterson, Deeds, and a few rare others who achieved big. Of those, the rarest bird was Wilbur Wright, his success cut short just as he achieved it.

Boss Kett gave us unleaded gas, diesels and the keys to the road. Crazy Patterson created the very model of the modern major corporation. Wilbur and Orville taught us to fly.

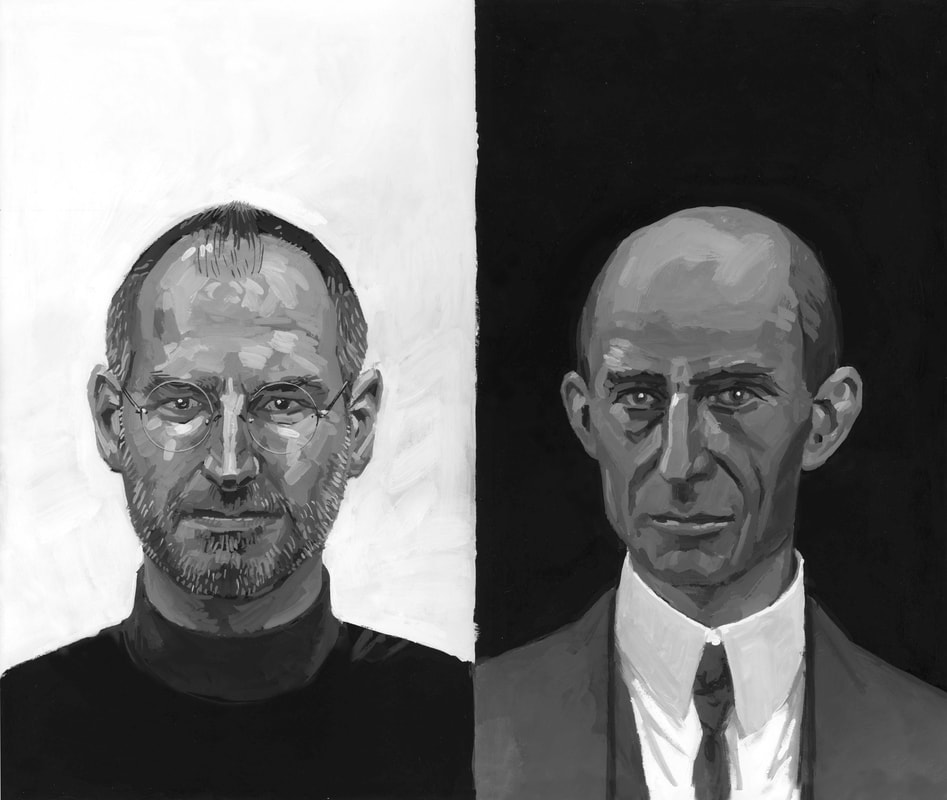

Always we’re told about the Brothers plural, as if they were clones. But Wilbur and Orville Wright were as different as the two founders of Apple Computer.

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak built the first Apple computers in a garage with modest savings and not much college under their belts. Woz focused on the technical innards while Jobs had the vision, bridged the gap with the business world, protected their innovations and put on killer demos.

That’s similar to Orville and Wilbur, except that Wilbur did his bit like a Buster Keaton silent movie, rarely opening his mouth in public while performing heart-stopping flights.

Wilbur hadn’t always been tight-lipped. Father Milton Wright made his boys argue topics at the dinner table like a couple of trial lawyers, then switch sides and argue the reverse positions. That was Milton, the bishop who sued his own church God knows how often. He traveled often so mother Susan taught her sons to tinker and fix things.

The result was a creative duo that could tackle technical problems by arguing through the roadblocks. “Tis too!” “Tisn’t either!” The air got so hot at times those around them feared violence, but the brotherly bond let them focus their dissent on the problem, not each other.

Wilbur was born in 1867 in Indiana and missed graduating high school when the family moved to Dayton in his senior year. Even so, he had been accepted to attend Yale University. Then one winter day a fateful hockey puck smashed his front teeth and his college dreams. Feeling his health too compromised to pursue a degree, Wilbur withdrew and cared for his invalid mother. She died three years later. By then Orville was building a printing press of his own design, and the project drew Wilbur out of his funk as they created a business. Then in 1892 they spotted a new tech craze: bicycles.

Like the Internet boom 100 years later, the new “safety” bikes provided radical new access to the world, especially women. Selling bikes didn’t seem to improve the brothers’ dating prospects. They remained single all their lives. Still, the bicycle shop did earn enough to finance their next enthusiasm, flying. But first death loomed anew.

In 1896 Wil and Orv had become avid followers of Otto Lilienthal in Germany, the world’s leading glider designer and flyer. Then in August Orville came down with deadly typhoid fever and spent six weeks bedridden. When Wilbur read of Lilienthal’s death in a crash he kept the bad news silent until Orville recovered. Meanwhile it lit a spark. Wilbur was 29; he’d survived his dental trauma but general life expectancy then was only 45. How would he be remembered?

Wilbur started reading about flight. By 1899 he was writing to leaders in the field about “my” plans. One letter started, "for some years I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man." Orville soon joined in the project. But Wilbur took the lead, then and later.

The brothers together solved the many problems of building a practical airplane. Probably neither could have pinpointed afterwards who did which parts of the work. But there were general differences. Wilbur could visualize a problem and turn it over in his mind. Orville was a whiz at mechanical tinkering and an athlete, winning bike races. Both had the tough, wiry build that would suit them to the hard physical work on the ground and piloting in the air.

Wilbur traveled first to North Carolina to test their glider. He did all the flying at first. Again, Orville followed his older brother and racked up his own glides to become equally skilled. Wilbur lost the coin toss that fateful day in December 1903, and Orville made the first official powered flight.

When the brothers returned to Dayton the flights got longer, higher and deadlier at Huffman Prairie. No longer flying low over soft sand, they learned to turn, climb, and stretch their flights to 40 seconds…5 minutes…by the end of 1905, 38 minutes. They had mastered practical flight with just cuts and bruises.

Plenty of other accounts detail how the Wrights invented flight. Suffice it to say that Wilbur and Orville solved a half-dozen major problems, including developing 3-axis control, researching the best wing shape, developing a light minimal engine, designing the first efficient propeller, and conducting a safe development process until they had a truly practical airplane. Only they seemed to truly realize that flight occurred in 3D, thinking outside the box.

Another way to slice it: Dayton’s Aviation Trail saluted four main Wright accomplishments: the first powered flight, the concept of wing warping and perfecting the wing’s shape, building the first aircraft factory, and creating the first permanent airfield at Huffman Prairie, which trained 119 pilots.

Once practical flight had been hammered out, Wilbur pursued patent rights and attempted to sell the plane. After months and years of disbelief by the outside world the Wrights won contracts with both the U.S. Army and a French syndicate. Both deals required public flights thousands of miles apart. Too much delay would let competitors catch up. So the brothers gambled and split up.

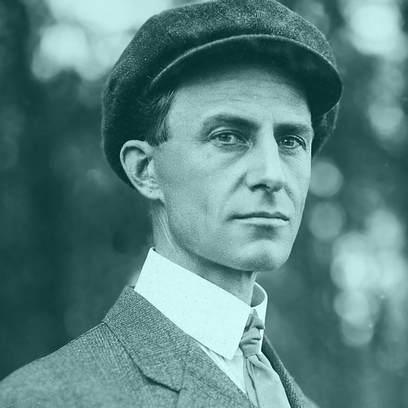

In 1908 Wilbur went to France. He faced language barriers, suspicion and his own reticence. Convinced the bicycle mechanic was a fake, Europeans were astounded when he took to the air. Soon huge crowds and royalty were showing up. Wilbur was suddenly, wildly famous. Every personal detail was analyzed, or as much as the press could get hold of from the reticent inventor—his plain clothes and cap, frugal living arrangements, nose-to-the-grindstone attitude.

Prodded by reporters, he said he “did not have time for both a wife and an airplane.” Toasted repeatedly, he avoided speechmaking by saying, “I know of only one bird—the parrot—that talks; and it can’t fly very high.”

The pressure was intense to attend every social invitation, interview and honorary dinner. Instead Wil kept his head down, mouth shut and took meticulous care of the craft —refusing to fly when conditions weren’t right, despite frustrating the crowds and VIPs.

A month later Orville made similar headlines flying before the U.S. Army. The shy, younger brother was battered even worse by the wild publicity. That may have contributed to the nasty crash that seriously injured him and killed his passenger. But within the year Orv returned to the air and won the Army contract.

The brothers ended their public demos in 1909 after Wilbur made a last spectacular flight down the Hudson River, past New York City, and around the Statue of Liberty. Altogether a million people witnessed their first flight.

Now famous as the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville tried to dodge a triumphal homecoming in Dayton but failed. The parade and grand celebration at the fairgrounds let everyone bask in the glory.

The brothers were world-famous and soon rich, winning $30,000 from the Army contract, worth nearly $700,000 today. By 1910 the Wright Company, with Wilbur at the head, was churning out Model B airplanes for $5000 a pop. A flying school was started, then an exhibition team. They planned a mansion in Oakwood. And Wilbur came to a fateful decision.

Steve Jobs was always obsessed by design, his eye constantly on the future. The Apple II pioneered personal computing; then the Macintosh introduced the graphical interface to the masses. Apple became an instant success before Jobs’ ouster in 1985. He had changed the world, made a bundle and was then “freed” for his most creative period founding Next Computers, Pixar, etc.

By contrast, Wilbur sacrificed the Wright lead in design to pursue patent infringements. To avoid jeopardizing their patent, the brothers resisted a newer, safer design that put the engine up front and protected the pilot in case of a crash. Such single-mindedness proved Wilbur’s fatal flaw, and it tarnished their public reputation as greedy moneygrubbers who spurned the “open source” approach. But the Wrights had spent years and risked their lives to perfect flight, and felt it unjust that others could use their work without payment.

The most aggravating example was Glenn Curtiss, a motorcycle racer who at first tried to sell engines to the Wrights and later built near knock-offs of the Wright design. Thus from 1910 onward Wilbur crisscrossed the country with his lawyers.

The road took its toll. Then in April 1912 came that fateful bowl of Boston chowder, or whatever it was that gave him typhoid fever. He limped home ill, then hovered near death for weeks before succumbing at age 45.

Dayton mourned Wilbur’s death on May 30, 1912. Their native son, who found fame overseas, was given a final procession up 5th Street before 25,000 people. The entire city held a collective wake as businesses closed, telephone exchanges were silenced and streetcars froze, all to the sound of church bells. “A short life, full of consequences,” Wilbur’s father wrote.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote “there are no second acts in American lives.” Steve Jobs was the rare exception, achieving more after his return to Apple. Had Wilbur Wright survived, what encore might he have achieved?

The Wright Company had a brief opportunity to regain the lead in aviation before WWI radically reshaped the airplane. Instead Orville sold the company and retreated from the limelight. Even so, Dayton remained a center for aviation technology. Today you can spot the ironic name of aerospace contractor Curtiss-Wright as you drive past Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

We’ll never know how history might have been. But clearly, this Memorial Day is a fitting time to celebrate the loss of one of Dayton’s most irreplaceable men. In five years we can more happily celebrate the 150th anniversary of his arrival.

What about Orville?

Orville Wright’s achievements after his brother’s passing highlight Wilbur’s side of the duo. In private a genial prankster, Orv was intensely shy in public. Never married, he proved a devoted uncle.

In 1914 Orville ended the patent fight with Curtiss after a minor court victory and sold the Wright Company. He built a private lab and continued to tinker on his own. Orville’s 1921 split-flap patent was far ahead of its time, and not appreciated until years later. He also invented toy airplanes that proved popular with kids. He fought the Smithsonian Institution until they gave proper recognition to the Wrights, finally bequeathing a Wright airplane to the museum in 1942. He also served for decades on aviation advisory groups.

Wilbur never saw the Oakwood mansion that became Hawthorn Hill. Orville lived there the rest of his life, alone after father Milton died in 1917 and sister Katharine married in 1926. The house contains many of his inventive touches, like a multi-jet shower and built-in vacuum cleaner system.

Orville Wright lived until 1948 to witness the supersonic jet age arrive; just 20 years after his death men circled the moon. During WWII a reporter ran into him on the street and asked about his legacy. Despite the growth of military aviation in two world wars, Orville felt—rightly—that the airplane would mainly prove a tool for peace.

Originally published in the Dayton City Paper

At rare intervals a few truly indispensable individuals take us where no one has gone before. A century back in Dayton it was Kettering, Patterson, Deeds, and a few rare others who achieved big. Of those, the rarest bird was Wilbur Wright, his success cut short just as he achieved it.

Boss Kett gave us unleaded gas, diesels and the keys to the road. Crazy Patterson created the very model of the modern major corporation. Wilbur and Orville taught us to fly.

Always we’re told about the Brothers plural, as if they were clones. But Wilbur and Orville Wright were as different as the two founders of Apple Computer.

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak built the first Apple computers in a garage with modest savings and not much college under their belts. Woz focused on the technical innards while Jobs had the vision, bridged the gap with the business world, protected their innovations and put on killer demos.

That’s similar to Orville and Wilbur, except that Wilbur did his bit like a Buster Keaton silent movie, rarely opening his mouth in public while performing heart-stopping flights.

Wilbur hadn’t always been tight-lipped. Father Milton Wright made his boys argue topics at the dinner table like a couple of trial lawyers, then switch sides and argue the reverse positions. That was Milton, the bishop who sued his own church God knows how often. He traveled often so mother Susan taught her sons to tinker and fix things.

The result was a creative duo that could tackle technical problems by arguing through the roadblocks. “Tis too!” “Tisn’t either!” The air got so hot at times those around them feared violence, but the brotherly bond let them focus their dissent on the problem, not each other.

Wilbur was born in 1867 in Indiana and missed graduating high school when the family moved to Dayton in his senior year. Even so, he had been accepted to attend Yale University. Then one winter day a fateful hockey puck smashed his front teeth and his college dreams. Feeling his health too compromised to pursue a degree, Wilbur withdrew and cared for his invalid mother. She died three years later. By then Orville was building a printing press of his own design, and the project drew Wilbur out of his funk as they created a business. Then in 1892 they spotted a new tech craze: bicycles.

Like the Internet boom 100 years later, the new “safety” bikes provided radical new access to the world, especially women. Selling bikes didn’t seem to improve the brothers’ dating prospects. They remained single all their lives. Still, the bicycle shop did earn enough to finance their next enthusiasm, flying. But first death loomed anew.

In 1896 Wil and Orv had become avid followers of Otto Lilienthal in Germany, the world’s leading glider designer and flyer. Then in August Orville came down with deadly typhoid fever and spent six weeks bedridden. When Wilbur read of Lilienthal’s death in a crash he kept the bad news silent until Orville recovered. Meanwhile it lit a spark. Wilbur was 29; he’d survived his dental trauma but general life expectancy then was only 45. How would he be remembered?

Wilbur started reading about flight. By 1899 he was writing to leaders in the field about “my” plans. One letter started, "for some years I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man." Orville soon joined in the project. But Wilbur took the lead, then and later.

The brothers together solved the many problems of building a practical airplane. Probably neither could have pinpointed afterwards who did which parts of the work. But there were general differences. Wilbur could visualize a problem and turn it over in his mind. Orville was a whiz at mechanical tinkering and an athlete, winning bike races. Both had the tough, wiry build that would suit them to the hard physical work on the ground and piloting in the air.

Wilbur traveled first to North Carolina to test their glider. He did all the flying at first. Again, Orville followed his older brother and racked up his own glides to become equally skilled. Wilbur lost the coin toss that fateful day in December 1903, and Orville made the first official powered flight.

When the brothers returned to Dayton the flights got longer, higher and deadlier at Huffman Prairie. No longer flying low over soft sand, they learned to turn, climb, and stretch their flights to 40 seconds…5 minutes…by the end of 1905, 38 minutes. They had mastered practical flight with just cuts and bruises.

Plenty of other accounts detail how the Wrights invented flight. Suffice it to say that Wilbur and Orville solved a half-dozen major problems, including developing 3-axis control, researching the best wing shape, developing a light minimal engine, designing the first efficient propeller, and conducting a safe development process until they had a truly practical airplane. Only they seemed to truly realize that flight occurred in 3D, thinking outside the box.

Another way to slice it: Dayton’s Aviation Trail saluted four main Wright accomplishments: the first powered flight, the concept of wing warping and perfecting the wing’s shape, building the first aircraft factory, and creating the first permanent airfield at Huffman Prairie, which trained 119 pilots.

Once practical flight had been hammered out, Wilbur pursued patent rights and attempted to sell the plane. After months and years of disbelief by the outside world the Wrights won contracts with both the U.S. Army and a French syndicate. Both deals required public flights thousands of miles apart. Too much delay would let competitors catch up. So the brothers gambled and split up.

In 1908 Wilbur went to France. He faced language barriers, suspicion and his own reticence. Convinced the bicycle mechanic was a fake, Europeans were astounded when he took to the air. Soon huge crowds and royalty were showing up. Wilbur was suddenly, wildly famous. Every personal detail was analyzed, or as much as the press could get hold of from the reticent inventor—his plain clothes and cap, frugal living arrangements, nose-to-the-grindstone attitude.

Prodded by reporters, he said he “did not have time for both a wife and an airplane.” Toasted repeatedly, he avoided speechmaking by saying, “I know of only one bird—the parrot—that talks; and it can’t fly very high.”

The pressure was intense to attend every social invitation, interview and honorary dinner. Instead Wil kept his head down, mouth shut and took meticulous care of the craft —refusing to fly when conditions weren’t right, despite frustrating the crowds and VIPs.

A month later Orville made similar headlines flying before the U.S. Army. The shy, younger brother was battered even worse by the wild publicity. That may have contributed to the nasty crash that seriously injured him and killed his passenger. But within the year Orv returned to the air and won the Army contract.

The brothers ended their public demos in 1909 after Wilbur made a last spectacular flight down the Hudson River, past New York City, and around the Statue of Liberty. Altogether a million people witnessed their first flight.

Now famous as the Wright brothers, Wilbur and Orville tried to dodge a triumphal homecoming in Dayton but failed. The parade and grand celebration at the fairgrounds let everyone bask in the glory.

The brothers were world-famous and soon rich, winning $30,000 from the Army contract, worth nearly $700,000 today. By 1910 the Wright Company, with Wilbur at the head, was churning out Model B airplanes for $5000 a pop. A flying school was started, then an exhibition team. They planned a mansion in Oakwood. And Wilbur came to a fateful decision.

Steve Jobs was always obsessed by design, his eye constantly on the future. The Apple II pioneered personal computing; then the Macintosh introduced the graphical interface to the masses. Apple became an instant success before Jobs’ ouster in 1985. He had changed the world, made a bundle and was then “freed” for his most creative period founding Next Computers, Pixar, etc.

By contrast, Wilbur sacrificed the Wright lead in design to pursue patent infringements. To avoid jeopardizing their patent, the brothers resisted a newer, safer design that put the engine up front and protected the pilot in case of a crash. Such single-mindedness proved Wilbur’s fatal flaw, and it tarnished their public reputation as greedy moneygrubbers who spurned the “open source” approach. But the Wrights had spent years and risked their lives to perfect flight, and felt it unjust that others could use their work without payment.

The most aggravating example was Glenn Curtiss, a motorcycle racer who at first tried to sell engines to the Wrights and later built near knock-offs of the Wright design. Thus from 1910 onward Wilbur crisscrossed the country with his lawyers.

The road took its toll. Then in April 1912 came that fateful bowl of Boston chowder, or whatever it was that gave him typhoid fever. He limped home ill, then hovered near death for weeks before succumbing at age 45.

Dayton mourned Wilbur’s death on May 30, 1912. Their native son, who found fame overseas, was given a final procession up 5th Street before 25,000 people. The entire city held a collective wake as businesses closed, telephone exchanges were silenced and streetcars froze, all to the sound of church bells. “A short life, full of consequences,” Wilbur’s father wrote.

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote “there are no second acts in American lives.” Steve Jobs was the rare exception, achieving more after his return to Apple. Had Wilbur Wright survived, what encore might he have achieved?

The Wright Company had a brief opportunity to regain the lead in aviation before WWI radically reshaped the airplane. Instead Orville sold the company and retreated from the limelight. Even so, Dayton remained a center for aviation technology. Today you can spot the ironic name of aerospace contractor Curtiss-Wright as you drive past Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

We’ll never know how history might have been. But clearly, this Memorial Day is a fitting time to celebrate the loss of one of Dayton’s most irreplaceable men. In five years we can more happily celebrate the 150th anniversary of his arrival.

What about Orville?

Orville Wright’s achievements after his brother’s passing highlight Wilbur’s side of the duo. In private a genial prankster, Orv was intensely shy in public. Never married, he proved a devoted uncle.

In 1914 Orville ended the patent fight with Curtiss after a minor court victory and sold the Wright Company. He built a private lab and continued to tinker on his own. Orville’s 1921 split-flap patent was far ahead of its time, and not appreciated until years later. He also invented toy airplanes that proved popular with kids. He fought the Smithsonian Institution until they gave proper recognition to the Wrights, finally bequeathing a Wright airplane to the museum in 1942. He also served for decades on aviation advisory groups.

Wilbur never saw the Oakwood mansion that became Hawthorn Hill. Orville lived there the rest of his life, alone after father Milton died in 1917 and sister Katharine married in 1926. The house contains many of his inventive touches, like a multi-jet shower and built-in vacuum cleaner system.

Orville Wright lived until 1948 to witness the supersonic jet age arrive; just 20 years after his death men circled the moon. During WWII a reporter ran into him on the street and asked about his legacy. Despite the growth of military aviation in two world wars, Orville felt—rightly—that the airplane would mainly prove a tool for peace.

Related

Valley of the Giants - Orville Wright

Wright Family Oral Histories

Dayton Aviation Heritage NPS

How We Made the First Flight

by Orville Wright

Flying and The Aero Club of America Bulletin, December 1913

My Acquaintance With Orville Wright—“An Unassuming American…”

By Col. Edward A. Deeds, As Told to A. S. Kany

Dayton Journal Herald on December 12, 1943

Aviators: The Wright Brothers

A Pair Of self-Taught Engineers Working In A Bicycle Shop, They Made The World A forever smaller place.

By Bill Gates, TIME, Mar. 29, 1999

Wright Brothers Collection, Wright State University Special Collections & Archives

Includes the Wrights’ own technical and personal library, family papers including letters, diaries, financial records, genealogical files, and other documents detailing the lives and work of Wilbur and Orville Wright and the Wright Family.

Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of CongressIncluded in the collection are diaries and notebooks, correspondence, scrapbooks, drawings, printed matter, and other documents, largely from 1900 to 1940, as well as the Wrights' collection of 303 glass-plate photographic negatives. The Wright brothers' letters to aviation pioneer and mentor Octave Chanute, from the Octave Chanute Papers, are also included.

The Wright Brothers and The Invention of the Aerial Age, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The first part of this exhibition tells the story of how Wilbur and Orville Wright invented the airplane—who they were, how they worked, and what they accomplished. The second part shows how their monumental achievement affected the world in the decade that followed, when people everywhere became fascinated with flight. The exhibition includes many historic photographs and cultural artifacts, along with instruments and personal items associated with the Wrights.

Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park

Three exceptional men from Dayton, Ohio, Wilbur Wright, Orville Wright and Paul Laurence Dunbar, found their creative outlet here through accomplishments and failures, and finally success. However, these men offered the world something far greater, they offered the world hope, and the ability to take a dream and make it a reality.

National Museum Of The United States Air Force

Ohio’s Aviation Heritage Teacher Resource Guide

The Wright Brothers' Dayton Documentary FilmThe Wright Brothers' Dayton highlights an extraordinary period in Dayton's history, the 1890's through the early 1920's, when inventors, entrepreneurs and visionaries called Dayton home. It was a time when men like John Patterson, Charles Kettering, Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Cox walked along the same city streets. Think TV

Wright Family Oral Histories

Dayton Aviation Heritage NPS

How We Made the First Flight

by Orville Wright

Flying and The Aero Club of America Bulletin, December 1913

My Acquaintance With Orville Wright—“An Unassuming American…”

By Col. Edward A. Deeds, As Told to A. S. Kany

Dayton Journal Herald on December 12, 1943

Aviators: The Wright Brothers

A Pair Of self-Taught Engineers Working In A Bicycle Shop, They Made The World A forever smaller place.

By Bill Gates, TIME, Mar. 29, 1999

Wright Brothers Collection, Wright State University Special Collections & Archives

Includes the Wrights’ own technical and personal library, family papers including letters, diaries, financial records, genealogical files, and other documents detailing the lives and work of Wilbur and Orville Wright and the Wright Family.

Wilbur and Orville Wright Papers at the Library of CongressIncluded in the collection are diaries and notebooks, correspondence, scrapbooks, drawings, printed matter, and other documents, largely from 1900 to 1940, as well as the Wrights' collection of 303 glass-plate photographic negatives. The Wright brothers' letters to aviation pioneer and mentor Octave Chanute, from the Octave Chanute Papers, are also included.

The Wright Brothers and The Invention of the Aerial Age, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The first part of this exhibition tells the story of how Wilbur and Orville Wright invented the airplane—who they were, how they worked, and what they accomplished. The second part shows how their monumental achievement affected the world in the decade that followed, when people everywhere became fascinated with flight. The exhibition includes many historic photographs and cultural artifacts, along with instruments and personal items associated with the Wrights.

Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park

Three exceptional men from Dayton, Ohio, Wilbur Wright, Orville Wright and Paul Laurence Dunbar, found their creative outlet here through accomplishments and failures, and finally success. However, these men offered the world something far greater, they offered the world hope, and the ability to take a dream and make it a reality.

National Museum Of The United States Air Force

Ohio’s Aviation Heritage Teacher Resource Guide

The Wright Brothers' Dayton Documentary FilmThe Wright Brothers' Dayton highlights an extraordinary period in Dayton's history, the 1890's through the early 1920's, when inventors, entrepreneurs and visionaries called Dayton home. It was a time when men like John Patterson, Charles Kettering, Paul Laurence Dunbar and James Cox walked along the same city streets. Think TV

Dayton Innovation Legacy is a multimedia website and educational resource about Engineers Club of Dayton members who represent a living history of innovation for over 100 years. Dayton Innovation Legacy was made possible in part by the Ohio Humanities Council, a State affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. |